Renewing Relationship Between Land and Culture

By Robin Wall Kimmerer

Robin Wall Kimmerer

Imagine for a moment, a beloved garden, where your grandma’s heirloom seeds are planted in old foundations that carry her memory, where the soil you have nurtured sustains your family, whose birds rely on your presence, where art adorns the fences. This a garden that you have tended for generations, learning more and more with every passing season until the knowledge of that place and the care for that place are inseparable from your being. A place you love and which loves you back, where your footsteps are as much a part of the garden as the rabbits. Now imagine being evicted from that garden, prevented from tending to its needs, watching its richness wither away under the hand of a new public lands manager who claims the right to do so, by his allegedly superior knowledge of production efficiency. Imagine that.

Let us acknowledge that what we call “public land” is also ancestral land, the source of life and well-being for indigenous peoples who played an integral role in maintaining its ecological vitality, producing not a “wilderness” but a cultural landscape, a home.

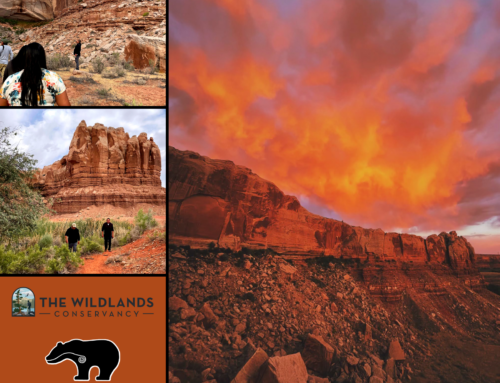

One such cultural landscape, known as the Bears Ears lies in the remote wilds of southeastern Utah, bordered by the splendor of Monument Valley and Canyonlands National Park. The 1.9 million acres of sandstone canyons, mesas, mountains and rivers shelter a wealth of over one hundred thousand archeological sites of rock art, kivas, granaries and other precious sites. Its diverse ecosystems have supported native peoples in subsistence and ceremony since time immemorial. This rich homeland of the original Navajo, Ute, Piute, Hopi and Zuni peoples remains unprotected and open to the exploitation which threatens many of our public lands- and is managed solely by the approaches of federal land policy.

In a visionary act of biocultural conservation, an intertribal coalition has proposed federal designation of the Bears Ears National Monument to protect this treasure in perpetuity. The Bears Ears would serve as a monument not only to the natural splendor of the region, but a monument to the native cultures who call it home and the knowledge they carry to care for it. Historically, designation of federal lands has been coupled with the eviction of native peoples, but at Bears Ears the tribes would instead renew their long-standing relationships with the land.

The Bears Ears National Monument would be remarkable for its protection of the past, but also for the future. It will protect not only a beautiful landscape, but cultural practices as rare and precious as an ancient village site; traditional land care knowledge. The monument would include shared management between the intertribal coalition and federal partners, using both traditional and scientific ecological knowledges for the first time on public lands. This brilliant symbiosis is at the cutting edge of visionary conservation practice. The Traditional Knowledge Institute proposed for Bears Ears offers an opportunity for powerful synergy between science and traditional knowledge, in service to the land which sustains us all.

Long before there was a Forest Service or the Bureau of Land Management, long before there was a federal government issuing natural resources policies; there was indigenous land care. Science offers a powerful approach for land management, but it’s not the only one. Native peoples tended their homelands with sophisticated stewardship based in traditional knowledge (TK), a deep understanding of place grown from long-term relationship with the land. It has been called “the intellectual twin to science” and includes what scientists would name as ecology, botany, zoology, pharmacology and natural resources management.

By its goals for pure objectivity, science intentionally keeps human cultural values out of the equation. But, TK is far more than observations and explanations of the living world. TK is both philosophy and practice, embedded in the indigenous worldview which guides right relationships between humans and the living world through the principles of respect, reciprocity, relationship and reverence. The living land is understood as far more than what scientists call natural resources, it is the source of identity, knowledge, the healer, the library, the sacred, the home of our ancestors and our more than human relatives. Humans are inseparably linked to land through a responsibility to give their own gifts, in return for all that the land so generously provides. Human gifts of gratitude, respect, attention, restoration, art, science, ceremony and care create a mutual symbiosis between people and land. Land is the place where we enact our moral responsibility to creation.

TK was long dismissed as invalid or irrelevant by the scientific establishment, but today scientists and policy makers all over the world have come to recognize its great value. International conservation norms call for the inclusion of TK as a vital conservation partner. The United States has an extraordinary opportunity to become a global example of the linkages between conservation and indigenous knowledge through establishment of the Bears Ears National Monument. This proposal is a stunning example of the potential for productive confluence of TK and western environmental science. Designation of the monument represents a turning point in land management, “one of the most ecologically and socially significant decisions ever created as a matter of conservation and Indian policy.”

Imagine what land would look like if managed by a creative symbiosis between indigenous land care and the tools of ecological sciences, land that reflects the gifts of mind, body, emotion and spirit. Wouldn’t it be a wild garden where humans and the more-than-human thrive together? A land that yields far more than a maximized output of commodities for industrial production? A place where all people can learn a new relationship with land, which is both ancient and urgent?

The monument takes its name from two rounded buttes that rise from the land like a bear about to raise its head over the horizon and look you in the eye. In my own Potawatomi culture, Bear is understood as a protector and a keeper of medicines. Designation of the Bears Ears National Monument is also protection – and medicine, a tangible sign of an intention for healing. For healing the land and human relationships to land are a step toward healing a troubled relationship, borne of a history which is painful for native people and shameful for settlers. Protection of the cultural landscapes, sacred places and ecosystems of the Bears Ears is a powerful step in restoring honor.

President Obama has an opportunity to right an historic and ongoing injustice, with far reaching consequences for land conservation. In designating the Bears Ears National Monument, the US would meet its trust responsibility to tribes and uphold the provisions of the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous People. This action can aid in healing the land and healing relationship among peoples by restoring rights of native peoples to jointly care for their homelands. Protecting this cultural landscape also invites settler society; todays’ citizens of the United States, to recognize that one day, they will also be named among the ancestors of these lands. They have a choice as to what kind of ancestors they wish to be. May we humans live in such a way that the land for whom we are grateful, will be grateful for our presence, in return.

Robin Wall Kimmerer is a mother, plant ecologist, writer, distinguished teaching professor, and serves as the founding director of the Center for Native Peoples and the Environment at the SUNY College of Environmental Science and Forestry in Syracuse, New York. Kimmerer’s interests in restoration include not only restoration of ecological communities, but restoration of our relationships to land. She is an enrolled member of the Citizen Potawatomi Nation and is the author of two books, “Gathering Moss” and “Braiding Sweetgrass.”